TopThe S.S. Patria

Accounts of its loss in 1899 and wreck fishing in 1910

This community website is regularly updated so click to refresh the page to see the latest content

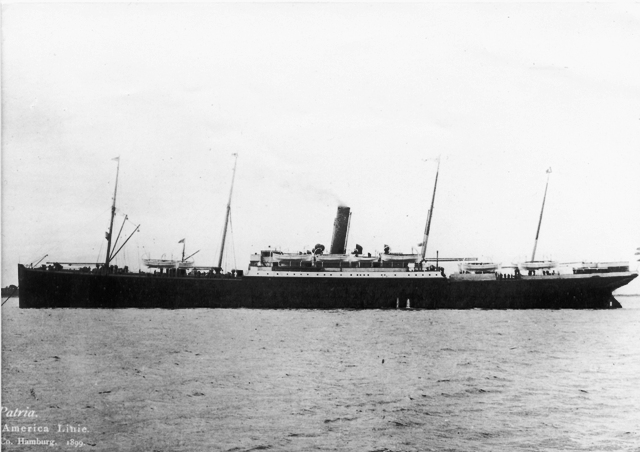

S.S. Patria

Steam liner weighing 7,188 tons built in Szczecin in 1894

Caught fire and eventually sank in the Downs in November 1899An account of wreck fishing off the S.S. Patria in 1910 with my father Alfred Barham Tooth

by Stanley Tooth

Dear Gillian,

This account has two parts, which will supplement what you already know about the adventurous side of my life. It begins with my earliest real adventure, which was linked to my father's special hobby, fishing - fresh-water and sea. His favourite venue, when I was young, was Deal (there were no motor cars or motor cycles in those days to take him to his later favourite fishing village, Boscastle). He usually fished from the Pier - very successfully, I may say - but, as often as he could afford it, he went boat fishing. In either case he often took me with him, even from the age of 10 or 11. I shall always remember vividly one particular expedition we made when I was in my very early 'teens. At Deal, my father knew a Mr. White, also a fisherman, who owned a sailing boat and who, for a price, would take people out fishing. He had not long come back from India, then a colony, of course. His first words to me, when he learned I was coming fishing with my father to fish in the Channel were, "You'll be all right, young man. I learned all about a much more cruel sea than this one, when I was abroad."

On the day in question, we were to fish off Deal over the wreck, deep down, of the S.S. 'Patria', a ship sunk there long enough before to have become the 'home' of many kinds of fish. "We're sure to catch some big 'uns", Mr. White told us, then, pointing on deck to a big bag of the beach shingle, tied to a long rope, he asked me, "What's that for?". When I told him I didn't know, he explained, "It's going to be our anchor. Whatever we use for an anchor will be caught up in the wreck and proper anchors cost money. So we use a bag of beach and, if we can't haul it up again, which nine times out of ten we can't, we just cut the rope when we want to leave."

We sailed from Deal on a gentle breeze and, when we were about a mile out and perhaps two miles along the coast, Mr. White said to me, "We find our wreck by looking for landmarks. Look straight at the shore. See that church spire in the distance ? See that yellow building much nearer ? Well, we have to get those two exactly in line. Then we want two other landmarks at a respectable angle to those. Look along the shore. See the coastguard station ? See that clump of trees on the hill-top a long distance behind it ? Well, we have to get those exactly in line, too." As he was speaking, he would now and again adjust the sail, besides attending to the tiller. "When we've got these two and those two exactly in line," he went on, "we should be over the 'Patria'. Mind you, what with the need to pinpoint the land-marks so accurately and also make allowance for the strong currents here, which vary with the rise and fall of the tide, we by no means always find the wreck first time. We can tell if we have, because if we haven't, we can raise the bag of beach easily." He turned to my father. "This is it, I think," he said, dropping the sail. "Overboard with the bag of beach, Mr. Tooth."

The rope seemed to run out a long way. "Yes, it's deep here," said Mr. White. "Test it, please, Mr. Tooth. See whether you can begin to pull it up again." When my father could not get the 'anchor' to move, Mr. White said, "Hang on, I'll come and help," but it made no difference. It seemed that we were well and truly anchored to the wreck. "Right!" said our friend, "We can start fishing."

From almost the first minute, we kept on catching fish but for some reason, it was my father and Mr. White who caught nearly all the big ones - skate, cod, congers, dogfish - while I drew up whiting and pouting. We had been fishing for perhaps half an hour, when Mr. White suddenly said, "I don't like this Mr. Tooth. The wind's getting up fast and look at those threatening clouds. I know what can happen here. It could soon blow a gale. We must start back." When my father, enjoying the unusually good fishing, demurred, Mr. White said reluctantly, "Well, a quarter of an hour. No, ten minutes. No more, but both of you put on your oilskins and sou'westers." He had already donned his.

Two or three minutes later, a particularly big wave nearly swamped the boat. With its anchor fixed to the bottom and the rope made fast to the deck, the boat couldn't rise high enough with the water and we shipped so much water that I was really scared. "Reel in, quickly, both of you," commanded Mr. White. Then, throwing a knife to my father, he signalled him to cut the rope, while he got busy with the sail. Only a couple of minutes passed before we were moving fast before the wind. The sail was out to one side at right angles to the wind and our boat was cutting square across the waves, rushing down the now deepening troughs and crawling up the other side of them. Now and again, a big wave or a gust of high wind would throw us off course, the boat would swing broadside on to the waves, roll alarmingly, and Mr. White would let go of the sail, so that it blew straight out with the wind, instead of flattening us into the sea. After he and my father had fought with the tiller to get us on course again, Mr. White would catch the end of the sail arm with a boat-hook and pull the sail round to catch the wind square again. Then we were cutting down and now even up the waves with the speed of an express train. "It's a gale force now!" Mr. White shouted to my father at the top of his voice and they both looked very serious. Then suddenly, without warning, rain blew from behind us in sheets, and, when we rode over the top of the next wave, I realised that both Mr. White and my father were searching through the rain to find something ahead. "We've got to miss the Pier!" I heard Mr. White shout to my father and, as he spoke, the rain stopped as suddenly as it had started. In a minute, Mr. White signalled to my father to take over the tiller, while he did more things to the sail. Every time we were high enough to see ahead, I strained my eyes to see the Pier, worrying whether the two men were managing to force the boat out to sea far enough, without the risk of her being blown flat. Neither of them tried to speak. Mr. White, sweating with his exertions, frequently signalled to my father at the tiller and, when we were about a hundred yards from the Pier, I saw there was a good chance we should miss it. Seconds later, we did by as much as 20 yards, and a small crowd of people sheltering at the end of the Pier, gave us waves as we sped by.

When Mr. White signalled to me to come to him, I stumbled and fell before I reached him. "Listen carefully," he yelled into my ear, "because we shall need your help. I'm turning the boat towards the shore because we've got to land here, where all those boatmen will help us. She'll be more across the waves and will roll a lot more but the Pier will break the waves somewhat. This is the drill. When we get near enough to the shore, I will try to get her on top of the right wave to carry us right up the beach. You and your father will each take an oar and sit on THAT side of the boat and I will drop the sail, take an oar and sit on THIS side. You can row, of course?" When I nodded, he went on, "Right! When I give the signal, we shall all row like hell, hoping to be carried up the beach on top of the wave and dropped there as it recedes. You needn't worry about getting out. Those men will lift you out as soon as they can reach you. Understand? Good! Go to your place, then, see where your oar is and be ready."

We did, indeed, roll a lot more in the lee of the Pier and more than once, as we sped in at an angle to the shore, I thought we were going to be blown flat. When we got nearer and I saw the murderous waves breaking on the beach, I knew what being frightened meant! - but, having a part to play in getting us on dry land again, did help. So did believing that Mr. White knew what he was doing.

Deal Pier Head, 1927Boat's-eye view in calm weatherIn no time, it seemed, we were on a big wave, high up, almost amongst the breakers. Then I saw Mr. White wave to us, grab his oar and, seconds later, the three of us were rowing as hard as we could to keep our boat on top of that wave. The next I remember was the boat crashing on to the beach, strong hands grabbing me and then pulling up my sou'wester so that I could see again. The boat, on its side, was being carried slowly down the beach as another big wave receded. Then the next wave moved it a few yards up the beach again. The sight of that raging sea was awe-inspiring!

From my high-up-on-the-beach place, I saw Mr. White and four of the boatmen hold on tight to the boat as the next wave approached. My father and the rest of the men were trying to rescue our belongings from the sea. One of the men dashed into the sea and came out again waving above his head one of the fish we had caught. Another man had got the boat-hook and my father was pulling on something he had picked up among the waves. In a minute or two, I saw what it was, for, jerking up the beach came one of our rods, with its reel still attached to it.

As I watched the scene, two of the boatmen came trotting down the beach, drawing two ropes with them. Then, as Mr. White busied himself fastening the ropes to his boat, the two me hurried back up the beach.

The men trying to retrieve our belongings were now having no luck. I could see that they had decided to give up, for they collected all the things they had retrieved, and brought them to where my father was still trying to disentangle his line and placed them together on the beach. There were two of the boat's four oars, our bait box, our rush fish bag (obviously empty!), a wet-through cardigan, two codfish, a dogfish, a skate, a conger eel and a whiting. Then, as the two men at the top of the beach began to work on the hand-winch they had commandeered, the boat began to move. First, it straightened up, then started crawling at a snail's-pace up the beach. When I told my father I was getting cold, he called all the men to him and tried to persuade them to take the fish between them. At first, they would have none of that but, when he explained that we and the people with whom we were staying couldn't possibly eat them all, Mr. White took the skate (which he had retrieved from the sea) and one of the boatmen took one cod, saying he would present it to 'old Mrs. English'. Then a kind man produced a piece of string and tied the other cod and the dogfish together by their gills and the conger and the whiting (my catch) in the same way, shouting to me above the gale, "Now you can walk home boasting!"

After my father and Mr. White had again offered their sincere thanks to the boatmen (most of whom seemed to think that what they had done was all in a day's work), my father, carrying one swaying rod, one bait-box and little else and I, with two heavy fish hanging from each of my hands, were blown into the side streets of Deal on our way to where we were staying. And what a relief it was! Away from the front, out of sight of the sea and with some protection from the incessant wind, it was like being in a different world!

Stanley Tooth, February 1990

Floating Furnace

By David Chamberlain

It was by the cold light of dawn that one hundred and fifty passengers from the Hamburg-American liner Patria abandoned ship. There was no panic, Captain Fröhlich and his officers supervised the evacuation and everything had been well organized. The passengers had been awoken at 6 a.m. on that Wednesday morning of the 15th November 1899 and were told to go, with haste, to their lifeboats stations. Some with only blankets draped over their nightclothes and others in various states of dress had no need to speculate the cause for concern. As they mustered around the steamship's eighteen lifeboats, smoke could be seen pouring out from the ships holds. Part of the Patria's cargo of wax and linseed oil was well ablaze. Standing by the burning ship were the vessels Ceres, Athesia and the Ramsgate fishing smack Adieu. They had been alerted by the flames coming from the vessel and helped in the rescue of the passengers.

The Patria had almost completed the last stage of her long voyage from America to Hamburg. Her position was a few miles from the North Hinder lightship; close to home but not close enough. As the day progressed, acrid smoke started to engulf the bridge, Captain Fröhlich ordered the rest of his crew to take to the safety of the lifeboats and awaiting ships.

Throughout the night he, with four of his officers and a few volunteers, remained fighting the fire. They did so until the wind shifted and the flames started to creep to the ship's stern, where they were struggling with the pumps. When the heat became unbearable they also abandoned the Patria and boarded the Athesia; which had stood by the floating furnace all night. After an assessment on Thursday morning the exhausted captain realised he could do nothing more. With reluctance he proceeded towards Hamburg in the Athesia, leaving the blazing ship drifting in the North Sea. As they approached Cuxhaven the Hamburg-American company tug Hansa was sighted and Captain Fröhlich was transferred aboard her. After a brief discussion it was decided to steam, at full speed, in search of the now abandoned vessel.

Eventually, at eight on Saturday morning, they sighted the still alight Patria some distance from the East Goodwin light vessel. As the Hansa approached she found two British steamers standing by the abandoned ship; they had tried towing her but their hawsers had snapped under the strain and heat. As the tug went alongside the Patria the crews were amazed to see six French fishermen perched on her bows. They had boarded the fiery derelict in hopes of salvage, but were only too glad to be relieved of their temporary command for the safety of a cooler deck.

Hansa was joined by the German tug Simson, whose offer of help was gratefully accepted, as the towing of the 6,664 ton vessel in her present condition was going to be hard work. The tugboat skippers decided that the best course of action would be to tow her to Deal, and beach her in the sheltered waters of the Downs.

The tugs thick wire hawsers held as the liner approached land. Her hull above the water line glowed white with heat. Every part of the wooden decks and fittings had disappeared, and her heavy cargo and machinery, buckled by the fire, had shifted and caused a pronounced list to starboard. As she was being towed through the shipping lane, opposite Walmer Castle, the ship's hull burst. At 9:30 on Sunday morning and five days after she had caught fire, the Patria's stern sank to the seabed. Steam, smoke and sparks were seen to bellow from the ship for hours. Her two after-masts toppled leaving only her funnel and forward mast preciously still standing; much to the bewilderment of the watching crowds, who had amassed along Deal's sea front.

Thick fog engulfed the Downs in the cold but light November airs.

Within days the Yarmouth-registered brigantine Eleanor had run into the part submerged hull of the Patria. The damage to the sailing ships port quarter was so extensive she had to be towed to Dover for repairs. The owners of the Eleanor, faced with a large shipwright's bill, had an Admiralty writ placed on the remaining mast of the Patria, to try for some compensation for the damage occurred. To make sure nothing was touched until a settlement was made a watchman was put in charge of the hulk. For him it was an uncomfortable job, at every high tide he would have to perch as far forward on the bows as possible and suffer the exposure of the Channel in winter. Under the charred and twisted remains of metal, iron beds and cooking utensils some of the valuable general cargo, amongst it being tons of copper, was still in the Patria's hold. A settlement was soon found, and as the customs officers removed the writ, the Copenhaven salvage vessel Emzsvilzer set about with her divers to try and patch up the holes in the wrecks hull.

As the fog cleared strong easterly winds briefly halted work on the burnt out shell. In the lulls of winter weather the salvors set about their task with fervour. Explosions rocked Deal and Walmer as the salvage team removed the jigger and mizzenmast which was still hanging over the submerged stern and hampered the divers' progress. The Danish hard-hat divers' skill and courage was greatly admired; to work in the dark murky waters which border the Goodwin Sands in the middle of December had to be tried to be appreciated.

For the men on the tugs, the heralding-in of the new twentieth century was just another working day. On Wednesday 3rd January 1900 the large Hamburg tugs Albatross and Seeadler were in position along side the wreck. As light faded Captain Spruth, the salvage master, and his divers were confident the Patria's holes had been patched up enough for a re-floating on the next day's high tide. The first glow of the weak sun lit the clamour of tugs and local boats as they bustled around the wreck. The pumps were rigged and started. On board the hulk were nearly twenty men. Some of them were the divers who had to unblock the suction pipe as it got choked up with part of the Patria's cargo of cooked, but soggy, grain and maize. Slowly the Patria's stern started to rise. The Seeadler had made fast to the bows of the ship and when her stern broke the surface the Albatross secured herself to it.

As the tide rose so did the blackened hull and shortly before noon the strong flood tide took possession of the powerful tugs' burden. The Patria went out of control as her bows swung to the southeast, nearly capsizing the Seeadler. The two tugs struggled with the 490 feet long ship; although the hulk seemed to have a will of its own. Within fifteen minutes she had gone with the tide and without warning started to sink, this time by her bow.

Amongst the pandemonium loud reports were heard, as her bulkheads and plates gave way. It happened quickly, and the ship completely disappeared under the water leaving all the men on deck struggling in the sea. Owing to the time of year many wore heavy clothing and leather sea boots, their salvation had to be quick or they would be dead. The local boats and tugs were prompt and did a good job amongst the chaos in saving most of the lives. Those who did not stand a chance were the chief diver Leopold Halfried who was pulled under whilst sitting in a small boat, which was tied to the Patria's stern. He had full diving dress on apart from his brass helmet, also two other divers and two local men perished. Every effort was made to retrieve the drowned men and they searched for the others until all were accounted for.

At the inquest Captain Spruth, the salvage master, was exonerated from any blame. He stated that he thought the ship would have floated after the repairs, and had used two of Germany's most powerful tugs. Also he had consulted local knowledge on the tides. It was a mystery why she had sunk. After a two week clearing up period the tugs had secured their pumps and other gear and left the Downs.

Throughout the summer months a Whitstable salvage company took over the wreck, recovering the copper and most of the other non-perishable cargo. It was then left to Trinity House authorities to disperse the wreck and make it safe for future shipping using the channel. This they did at a reputed cost of £6,000 and on the 2nd January 1902 the wreck marking lightship was removed from the site.

Copyright © David Chamberlain 2016

Deal, Walmer & Sandwich Mercury, Saturday, 3rd January 1903

The Sunken Wreck of the Patria

At last there is nothing left to remind us of the burning of the Patria, and the second disaster which was even more regrettable, inasmuch as it was accompanied by lamentable loss of life.

Every indication of the wreck was removed on the morning of the first of the new year. The gas bell buoy, as well as the three smaller buoys which have been in position near the Deal Pier ever since the wreck lightship was removed, was taken away on Thursday morning by the Trinity tender steamer, and there is now no danger anticipated.

At dead low water thirty seven feet represents the depth of water over the wreck, and this is sufficient for the largest vessel to pass over without any inconvenience.